unity amidst diversity: labor, race and religion

by Kenneth C. Burt

|

Today we recognize the bonds that unite Jewish workers with the larger labor movement, ethnic and racial minorities, and the faith community as we seek to follow the ancient command "to repair the world" (tikkun olam in Hebrew).

Only months ago, in November 2005, allied groups rallied to defend the integrity of public service and the right of organized labor to participate in civic life. The labor-led response to Governor Schwarzenegger's assault on teachers, nurses, firefighters and public safety officers resulted in the defeat of his three mean spirited voter initiatives — and the renewed recognition of the power of labor-minority-religious coalition politics.

The broad-based labor coalition included AFL-CIO unions, Change to Win affiliates, and independent groups such as the California Teachers Association (CTA) and a number of public safety groups. The campaign likewise placed an emphasis on working with the Asian, African American and Latino legislative caucuses and the Jewish network that includes Assembly Education Chair Jackie Goldberg and Assembly Labor Committee Chair Paul Koretz. The campaign likewise reached out to minority and religious groups with whom coalition members had worked in recent years.

Jewish labor activists worked through their unions and the Alliance for a Better California, the mega coalition leading the campaign against Propositions 74, 75 and 76. The JLC engaged a number of Jewish groups, including Amienu (Labor Zionist Alliance), Na'amat, Sholom Community Organization, and Workman's Circle, and worked with the Alliance to publish an ad in the Jewish Journal.

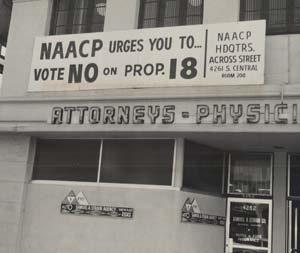

There is precedence for such unity. In 1958, when organized labor faced Proposition 18, the so-called Right-to-Work initiative, labor likewise rallied. At that time the AFL and CIO were separate organizations in California, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) and Internat

ional Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) were unaffiliated. Los Angeles labor took its message to minority communities with the help of Assemblyman Augustus Hawkins, the lone African American solon from Southern California, and Los Angeles City Councilman Edward Roybal.

As in earlier times, coalitions emerge out of shared values and mutual interests as well as inter-personal and inter-organizational relationships.

ongoing struggle

The November 2005 Special Election represented the fifth major attack on organized labor at the ballot box in modern California. Rightwing ideologues previously pushed voter initiatives in 1938, 1944, 1958 and 1998.

The 1938 fight, coming four years after the San Francisco General Strike, followed on the heels of the second coast wide job action led by ILWU's Harry Bridges; it sought to limit picketing and boycotts. The 1944 bill sought similar restrictions. The 1958 ballot initiative would have made California a Right-to-Work state under Taft-Hartley; it limited collective bargaining and prohibited mandatory union dues. The 1998 attack, Proposition 226, was crafted to take unions out of state politics.

On a partisan level, three of the four campaigns coincided with a gubernatorial election. In each case, the Republican Party nominee embraced the anti-labor initiative. The resultant mobilization of the labor vote, magnified by the support of community allies, contributed to the defeat of the initiatives and to election of three Democratic governors: Culbert Olson, in 1938; Pat Brown, in 1958; and Gray Davis, 1998.

In the fourth election, which shared the ballot with President Roosevelt in 1944, Governor Earl Warren, a moderate Republican, opposed the initiative, saying that it was bad policy and disrupted the homefront unity needed to defeat Hitler. Another moderate Republican, outgoing Governor Goodwin Knight, opposed Right to Work in 1958 even as William Knowland, the GOP gubernatorial nominee made it a central part of his campaign.

The elections — and the building of multi-cultural alliances — also resulted in civil rights advances, starting in 1938. Pledging to bring the New Deal to California, Olson appointed the first African American and the first Latino to the state bench. Governor Olson was likewise the first to place a significant number of Jews in administrative posts, including barrister Stanley Mosk, named as a gubernatorial aide before being offered a judicial post. Mosk became the first Jewish statewide elected official in 1958, as attorney general. He is remembered as one of the most notable members of the California Supreme Court and his statue overlooks the entry to the old court building in Sacramento. He also served as President of the Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles and participated in the Jewish Community Relations Council.

jlc and coalition politics

The JLC, founded in 1934 by Yiddish-speaking garment workers determined to fight the growing threat of Nazism in Europe, is a longtime partner in labor concerns — including issue-oriented ballot fights. The organization played a central role in the 1958 Right-to-Work struggle because of its unique position at the nexus for the labor-minority-religious civil rights coalition leading the fight to adopt state anti-discrimination laws.

The California Coalition for Fair Employment, founded in 1953, grew out of regional efforts to eliminate bias on the job. This new coalition jelled in Los Angeles in 1949 as it rallied behind Councilman Roybal's proposed Fair Employment Practices ordinance. While the measure narrowly failed, the vigorous campaign, chaired by Judge Isaac Pacht, an activist in the Jewish community, represented the first joint effort of the AFL Central Labor Council, the CIO Council, and a multitude of minority groups. These included various Jewish organizations (JLC, Anti-Defamation League, American Jewish Congress), the NAACP, the Japanese American Citizens League, and the Mexican-American oriented Community Services Organization (CSO). The JLC in this era wore many hats: in addition to participating in its own name, the JLC staffed the Labor Council's civil rights committee, and was organically tied to the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), which provided the only female organizer to the 1949 drive.

The California Coalition for Fair Employment broadened these ties. C.L. Dellums, uncle of former Congressman Ron Dellums, from Oakland, chaired the body, representing the AFL Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the NAACP. Councilman Roybal served as a vice chair along with construction worker Neil Haggerty, leader of the California Federation of Labor, and steelworker John Despol of the California CIO Council. Highly placed Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and Quaker leaders likewise served. Two JLC staffers with experience in labor and the liberal-left, Max Mont and Bill Becker, staffed the committee in Los Angeles and San Francisco respectively.

It was natural to utilize these networks and relationships to fight off the full-throttled attack on labor's right to bargain collectively and to collect membership dues. For while labor's record was imperfect, a number of unions had taken the lead in advocating for workplace fairness, elected minorities to union posts, and partnered with CSO and the NAACP to advocate for labor-community alliances.

To rally the civil rights community in Los Angeles, the labor movement brought in A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the "father of the FEPC" during World War II. Randolph, like the JLC leaders, had ties to the Socialist Party prior to the Roosevelt's New Deal; he served on the AFL Executive Council with JLC and ILGWU President David Dubinsky.

A. Philip Randolph keynoted a two-day Labor Conference on Human Rights at the Statler Hotel in early October 1958. CSO, NAACP, and the JLC co-sponsored the conference with the Central Labor Council, with JLC Executive Director Max Mont coordinating the event. Speakers included Jewish garment union officials, Assemblyman Hawkins, Councilman Roybal, and many others, including representatives of the co-sponsoring organizations. The labor-minority coalition reaffirmed their commitment to defeating the anti-labor initiative and to enacting fair employment legislation after the election.

The campaign also organized rabbis, priests and ministers to oppose Proposition 18, making it a moral imperative. The JLC's partner in the Catholic community, the Catholic Labor Institute (CLI), played a key role. Gubernatorial candidate Pat Brown joined Bishop Alden Bell and hundreds of Catholic trade unionists at the annual Labor Day Mass and Breakfast, where the church's pro-labor social gospel was reiterated. CLI's patron within the hierarchy was the Right Reverend Monsignor Thomas O'Dwyer, a California Committee for Fair Employment vice chair, who collaborated with the Jewish and Latino garment workers to elect Roybal to the city council.

Such relationships paid multiple dividends. Organized labor formed the Eastside Committee to Save Our State. A Latino unionist, James Cruz, headed the committee; Dave Fishman, from the Jewish Painters in Boyle Heights, served as the coordinator. The No on 18 group kicked off its election outreach with a Saturday afternoon car caravan that snaked through the working class neighborhoods of Boyle Heights and Lincoln Heights raising awareness of the election and stopping at major shopping centers to distribute information to voters. Three days later, the group sponsored a rally at the Jewish Carpenters Hall at Brooklyn and Soto Streets.

The JLC also reached out to the Jewish business community, which still suffered the sting of discrimination. Some law firms in Los Angeles, for example, still recruited young associates solely from the ranks of Protestant graduates. And outside of Hollywood, where they were a significant presence, Jews remained a rarity in the private sector unless self employed. A number of entrepreneurs associated with the JLC and the Workmen's Circle, an affiliated fraternal organization that helped the JLC, which likewise shared roots to the Socialist Bund in Eastern Europe, operated factories in the garment, shoe and furniture industries.

Others found a niche in the service sector. Benjamin Swig, proprietor of San Francisco's Fairmont Hotel, signed the statement against Right-to-Work initiative in the ballot pamphlet along with the AFL and CIO leaders. Swig's prominence in the fight underscored the linkages between labor and civil rights — and the very large Jewish role — in 1950s California.

labor and civil rights

On Election Day the voters trounced Proposition 18 and gave Pat Brown a million-vote margin as part of an historic Democratic landslide unimaginable just a few years earlier. Post-election analysis of the returns demonstrated that unionists, African Americans, Mexican Americans and Jews were overwhelmingly against Right-to-Work.

Upon assuming office in January 1959, Governor Brown and organized labor kept their commitment to make fair employment a top priority. The Governor stated in his inaugural address that "Discrimination in employment is a stain upon California" and urged the legislature to act.

Inside the Capitol, Jess Unruh, the Texas-born assemblyman who had run Brown's campaign in Southern California, shepherded the bill through the Lower House. The Assembly included a lone Jewish legislator from Los Angeles, the newly elected Tom Bane from the San Fernando Valley. (Jews had relinquished the Boyle Heights assembly seat but not yet become a force on the Westside.) Governor Brown used his influence in the rural dominated State Senate.

External pressure for the long sought measure came from the California Committee for Fair Employment, and its constituent groups, particularly the AFL and CIO unions that enjoyed enormous influence given the lopsided defeat of Proposition 18 and their support for the new Democratic legislative majority.

The chief lobbyist for fair employment, the JLC's Bill Becker, emphasized the importance of the liberal-labor coalition in passing the landmark civil rights bill in a Legislature with a dearth of Jewish solons, and only two African Americans, Hawkins and Byron Rumford. There were no Latino or Asian members. Brown signed the measure, which was particularly memorable because it was his first bill. Mont and Becker participated in the bill signing with select legislators and Black leaders.

Brown also named C.L. Dellums, chair of the California Committee for Fair Employment, to the board responsible for overseeing the implementation of the new law, along with Carmen Warshaw, a Los Angeles-based Jewish businesswoman and civil rights supporter. (The JLC honored Warshaw on the fiftieth anniversary of the Fair Political Practices Commission, along with Edward Roybal and Augustus Hawkins.)

past as prologue

The fight for a better world continues. By building upon past victories, like those of 1958 or 2005, we are able to overcome the inevitable setbacks. What remains consistent through the years is that no group in society is strong enough to protect its civil rights or economic standing alone. All groups, but particularly organized labor and ethnic, racial and religious minorities, require allies to overcome hurdles and to repel direct attacks on their communities. In unity there is strength.

Kenneth C. Burt is political director of the California Federation of Teachers. He has an essay in the new anthology, City of Promise: Race and Historical Change in Los Angeles.